This post was syndicated from the Inner Drive blog.

Giving feedback can be a double-edged sword. The Sutton Trust reports that if it is done right, it can be one of the most effective ways to help someone improve their learning; however, research suggests that 38% of feedback interventions actually do more harm than good.

What we intend to be encouraging and constructive can easily be interpreted as judgement and criticism. So how can we save ourselves from the pitfalls of giving unhelpful and potentially damaging feedback?

Don’t delay too much– An interesting review on when to give feedback found something quite curious. The researchers discovered that in experiments conducted in a laboratory, delayed feedback were more helpful; however, in a real world setting, especially in classrooms, immediate feedback was more beneficial. This makes sense when you think about it: the real world is messy and complicated; leave things too long and things get forgotten; memories get distorted; other pressing events crop up.

It is not always possible or practical to give immediate feedback. This is especially true if emotions are running high. The trick is to give timely feedback in a way that doesn’t smother people (too much too soon can be just as bad), but early enough that the event is still fresh in their mind. As with all things in psychology, there are some caveats to the rules.

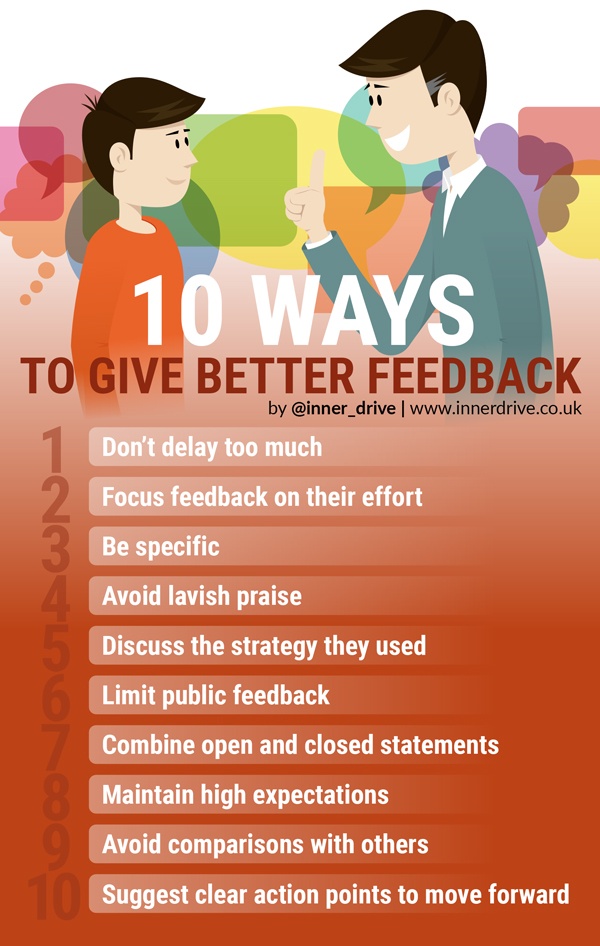

Here are ten tips on how to give better feedback:

Research suggests that in some situations, delaying feedback may actually be better. These may include when the task is simple and when there is plenty of time available (giving the other person enough time to try several different strategies)

Be specific – When you say ‘good’, the assumption is that the person will know exactly what was good. This is not always the case. It is easy for people to misunderstand what you mean. This is especially true when giving feedback to teenagers, who as a result of their brain restructuring, can find it harder to understand someone else’s perspective and thought process. The more detailed and specific the better. This will remove any ambiguity. It is far better to say, ‘The way you did X was really good.’

Focus feedback on their process, not their natural ability– Praising someone’s effort (instead of their intelligence) will help them to develop a growth mindset. This impact has been found in even very young children, with the type of praise given to 1-3 years old impacting on if they have fixed or growth mindset up to 5 years later.

Praising someone’s effort increases their intrinsic motivation and provides a template for them to follow next time. A separate study found that the type of praise children receive actually drives the type of feedback they then seek out themselves post task. In this study, 86% of children who had been praised for their natural ability asked for information about how their peers did on the same task. Only 23% of children who had been praised for effort asked for this type of feedback, with the vast majority of them asking for feedback about how they could do better.

Avoid lavish praise – When someone has repeatedly struggled, it is tempting to heap lots of praise on them when they achieve some level of success, no matter how small. This can actually do more harm than good. Insincere praise is very easy to detect. Too much praise can convey a sense of low expectation and, as a result, be demotivating.

Limit public feedback – Teenagers care a lot about what their peers think of them. Public feedback, even if well intended, can easily be interpreted as a public attack on them and their ability. This can quickly lead to a fear of failure. This can result in teenagers putting on a front, accompanied with bundles of bravado.

A nice way to overcome this is what author Doug Lemov calls ‘Private Individual Correction’. This limits the publicness of the feedback, whilst still getting the message across clearly. This is similar to the technique he calls ‘The Whisper Correction’, which although done in public, the pitch and tone of voice is done to limit everyone else’s attention to the individual feedback.

Combine open and closed statements – A closed question is one where the answer is ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (i.e. ‘Were you nervous before the exam?’). The problem with these questions is that if the answer is no, the conversation can grind to a halt. You may find out that they weren’t nervous, but you won’t find out what they were actively feeling (sad, angry, not bothered, tired etc.). An open question, such as ‘how were you feeling in the morning?’, encourages someone to tell their story.

A combination of open and closed questions and statements can help when it comes to giving feedback. Closed statements help you to convey the information you want and can potentially save time and keep the conversation focused. Open questions allow for a good two-way conversation and can help students develop a sense of ownership of the situation.

Avoid comparisons with others – It is far better to focus your feedback on their individual development and improvement instead of in comparison with others. A recent study found that being positively compared to someone else can lead to narcissistic behaviour. This sort of comparison can also reduce someone’s intrinsic motivation, which has been associated with lower confidence, emotional control, academic performance and increased anxiety.

Discuss the strategy they used – This can help them identify helpful thought processes so that they can do the same again next time. Psychologists call this ‘metacognition’. Put simply, metacognition is the awareness and control of your thought process. This is a very valuable skill and has been found to significantly help students improve their grades.

Maintain high expectations – A famous study, conducted almost fifty years ago, found that high expectations can have a powerful effect. Teachers were falsely told that some of their students had been identified as potential high achievers; they were expected to bloom over the course of the year. Several months later, when compared to the rest of their classmates, these students had in fact made significantly more progress. What drove this change? The teachers’ increased expectation for these students.

This is known as the Pygmalion Effect (named after the mythical Greek sculptor who loved his statue so much that it actually came to life). Have high standards and people will often up their game in order to match them. Sometimes students need someone to believe in them before they can believe in themselves.

Suggest clear action points to move forward – This is one of the key points from the ‘What Makes Great Teaching Report’. Feedback that doesn’t lead to behaviour change is redundant. There must be a point to it. What do you want them to do differently? What are they going to do after this conversation to improve? The more detailed and specific the action points the better.

FINAL THOUGHT

Giving feedback isn’t easy. If done right, however, it has the ability to transform someone’s learning and performance. If done wrong, it can actually do more harm than good. So don’t delay, focus on their effort, be specific, avoid lavish praise, limit public feedback, use both open and closed questions, avoid comparisons with others, and suggest clear action points moving forward.

This article was first published on The Guardian website on 10.11.16. You can read it, alongside all of our other Guardian blogs here: https://www.theguardian.com/profile/bradley-busch

About Inner Drive

InnerDrive is a mental skills training company coveing the traditional areas of sports psychology and mindset training.

Their work covers the traditional areas of performance psychology, sports psychology and neuroscience. They work with over 120 schools in England and last year worked with over 25,000 students, teachers and parents.

The company is led by Edward Watson, a retired Army major and Bradley Busch, a HCPC registered psychologist.